Why did my chemotherapy stop working? Your oncologist doesn’t have the time to give you an answer – but I do. I’m going to give you one look at how chemotherapy works. Chemotherapy changes the tumor. Understanding this allows you to prepare for the next question: what do I do next?

When I first learned this information, frankly it was somewhat depressing. I’m reminded of Simon Wardley’s graph of knowing versus expertise. A little knowledge is dangerous. A little more can be empowering.

For example, I’m disappointed when people glance at the dismal survival statistics and say that they’re not a statistic. Guess what? I’m a long term survivor and I’m in those statistics. There’s knowing the statistics and then there’s understanding the statistics. I admit that at first look the statistics is quite depressing. But a deeper look at the statistics reveals the story of the survivors. Understanding that story uncovers the path to be a survivor.

So let’s try to walk you through the area of a little knowledge to the area of understanding where there is hope and guidance. On to the land of survivors!

How a Tumor Cell is Made

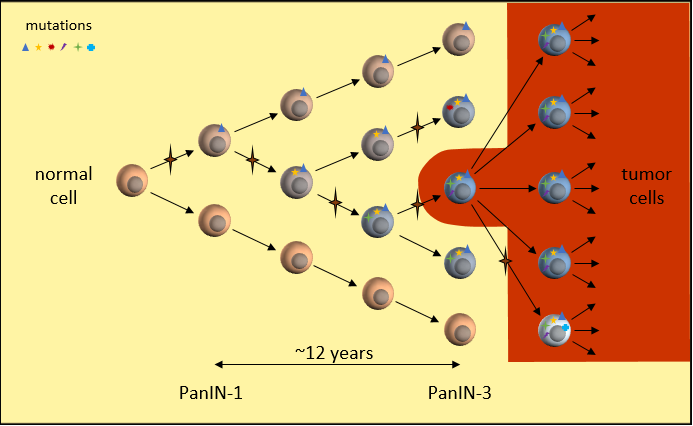

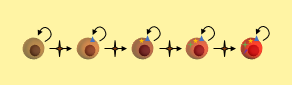

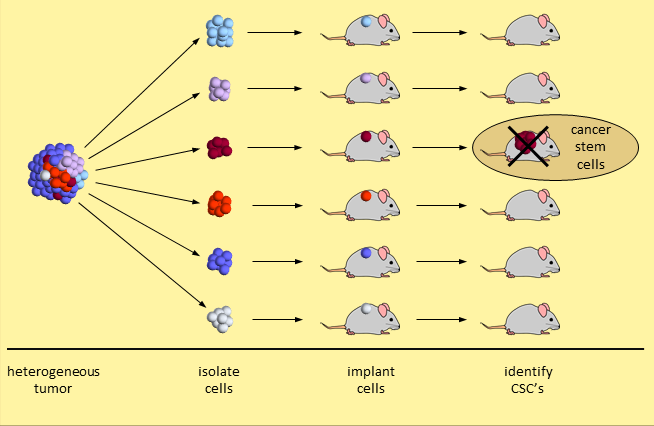

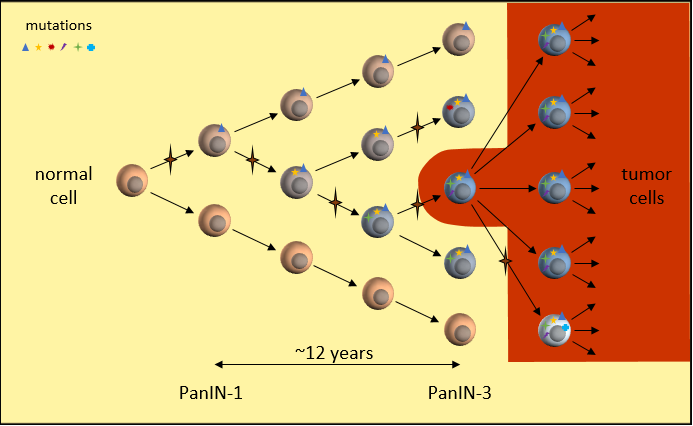

In the clonal evolutionary cancer model, a normal cell gains a set of mutations over time. These mutations could happen during cell division (mitosis), when a cell divides into two cells. A random mistake in the replication process means that one of the two “daughter” cells receives a mistake in its copy of DNA. The starred arrows denote these mutation events. Here, one daughter cell gains a mutation while the other does not.

Pancreatic Cancer Mutation Progression

DNA mutations can block the building of proteins critical to proper cell function. For instance, a mutation halting the production of proteins necessary for cell repair makes the cell susceptible to even more mutations. You may have heard that the KRAS gene is mutated in about 95% of all pancreatic cancers. This would be how one of these mutations might happen.

As this mutated cell splits further, these mistakes are copied to both “daughter” cells. When these cells split, another mutation may happen during replication that brings these cells another step closer to becoming a tumor cell. Each time we move to the right, one of the cells has gained a new mutation.

In pancreatic cancer, it takes around 12 years1 and at least a dozen of these mutations to disable the built-in protection mechanisms in the human body and create a tumor cell. Fortunately, it is an extremely rare set of circumstances. But not rare enough.

The takeaway:

Tumor cells have multiple DNA mutations that make them cancer cells

How a Tumor Grows

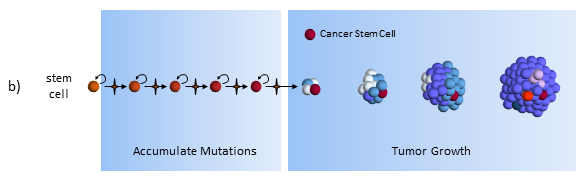

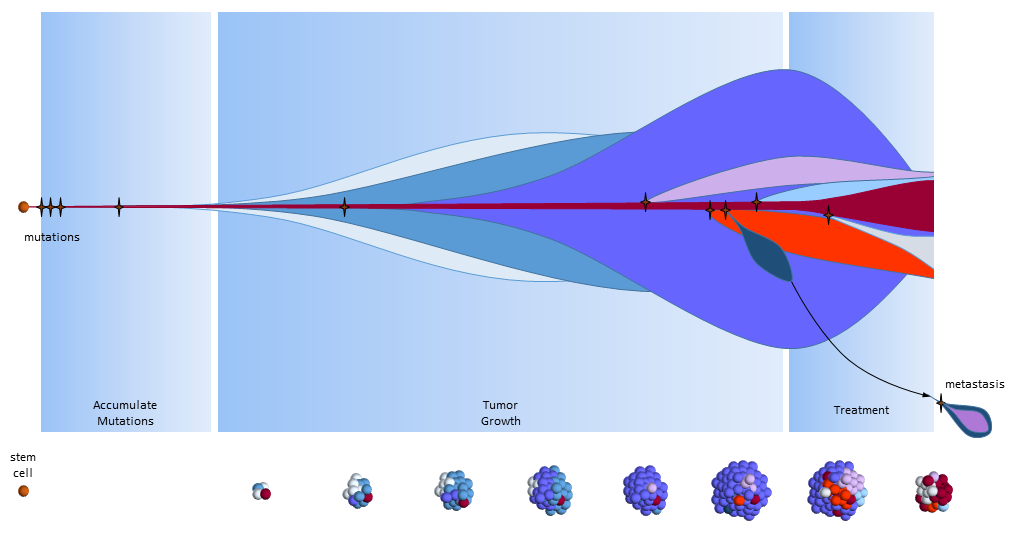

By the time the cell is cancerous, it has accumulated many mutations. One mutation allows the tumor cell to grow uncontrollably and a tumor cell can divide many more times than a normal cell. Another mutation breaks the verification checks on DNA replication, resulting in more and more mutations as it divides. Still another mutation prevents the immune system from recognizing the cell as unwelcome.

Many mutations are incompatible with survival and these cells die off quickly. But a few mutations provide a new advantage over the parent cells. This is an evolutionary process played out very rapidly. Many new mutations happen throughout the tumor to try their luck at survival. The tumor cells best able to reproduce begin to dominate by numbers. The result is a heterogeneous tumor. The tumor cells are not identical copies of the first tumor cell. Each succeeding generation of cells add more DNA mutations and possibly even changes some of the original mutations.

Tumor Growth

Over a period of around 7 years1, the tumor grows large enough to cause symptoms and be detected on scans. This cancer has been growing quite slowly and for a long time. It has been forming over the last two decades. This is one reason why pancreatic cancers occur relatively late in life (average age: 65 years old).

This may be the most important takeaway:

the tumor is heterogeneous, composed of tumor cells that are not genetically identical

Why is that important? Because each tumor cell may respond to treatment differently.

Treatment Selection

After the tumor has been detected and confirmed as cancer, we often select a treatment based on chemotherapy. In pancreatic cancers, we have almost no clue which treatment will be best. One major exception is a tumor with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation.

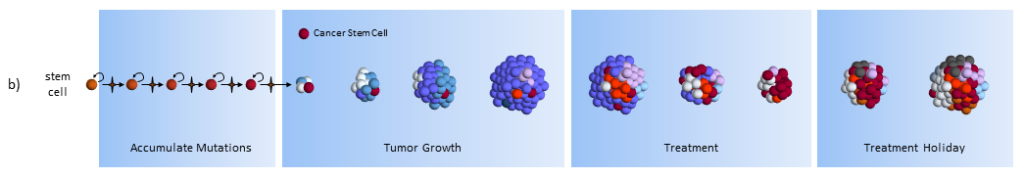

Treatments may only be effective on tumor cells with specific mutations. When chemotherapy is active in the body, cell division slows, but when divisions happen, new mutations continue to be generated. Some new mutations may find a way to get around the treatment and continue growing despite the treatment. These cells out-reproduce the other tumor cells. It’s an evolutionary survival of the fittest of tumor cells.

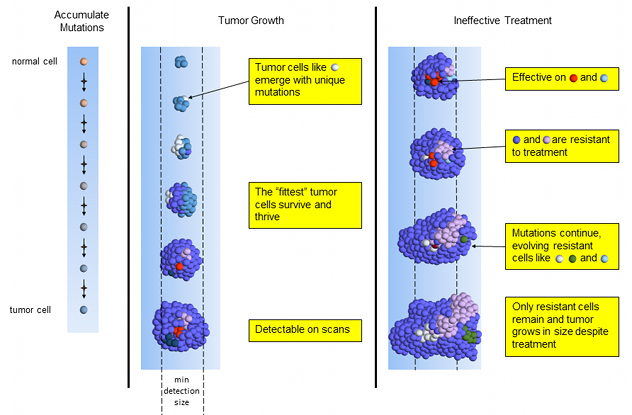

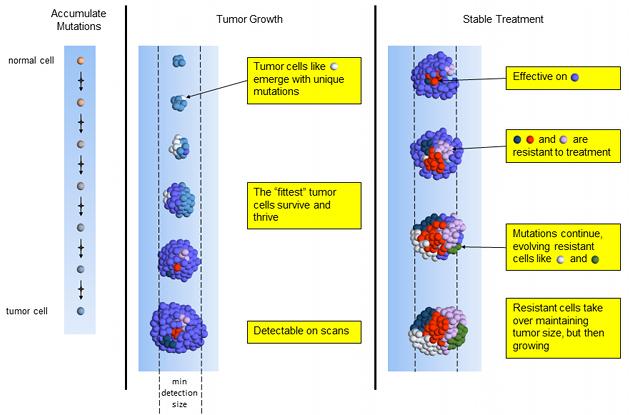

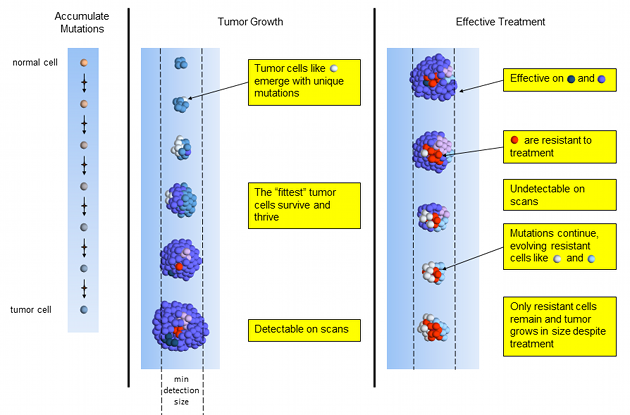

Let’s review ineffective, stable, and effective treatments to understand why the tumor responds the way it does. In these figures, the colors represent tumor cells with different sets of mutations.

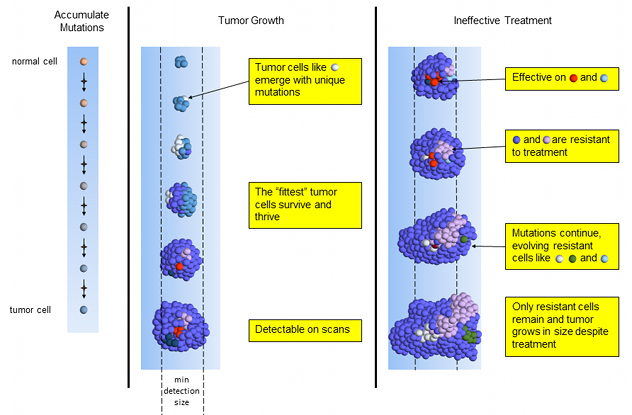

Ineffective Treatment

Ineffective chemotherapy works only on a small set of tumor cells (red and light blue). The dominant blue and rarer pink tumor cells resistant to treatment and continue to divide. The blue and pink cells generate new mutations, creating the white and green cells resistant to the treatment.

As the few susceptible cells die off, the unaffected cells continue reproducing. The tumor consists of mainly the same types of cells as when treatment started, plus some with new mutations. On scans the tumor is seen to be growing and it’s time to select a different treatment.

Ineffective Tumor Treatment

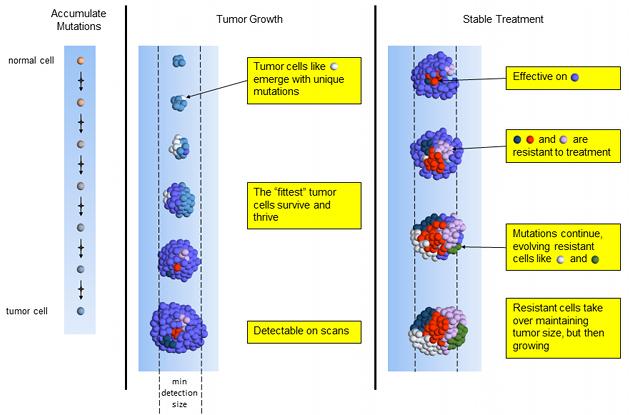

Stable Treatment

This chemotherapy is effective on the dominant blue tumor cells – which is good news! However, most others (red, dark-blue and pink) are resistant to treatment. Resistant cells replace dying cells and the tumor stays about the same size. More treatment-resistant cells emerge as mutated versions of previous tumor cells.

Stable Tumor Treatment

While the tumor is about the same size, the cell mutation composition is completely different than when treatment started. It is now dominated by cells that are resistant to the treatment and will begin growing again. We don’t have sufficient information to know when the treatment may fail. The tumor’s overall size may remain stable for months or even years. Many oncologists will continue the same treatment on this tumor until it is bigger or the patient can no longer handle the side effects.

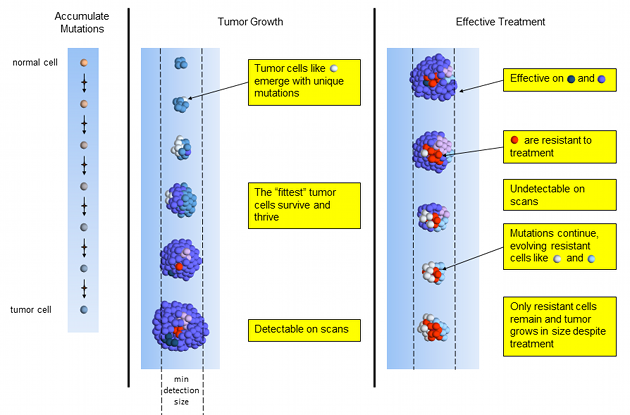

Effective Treatment

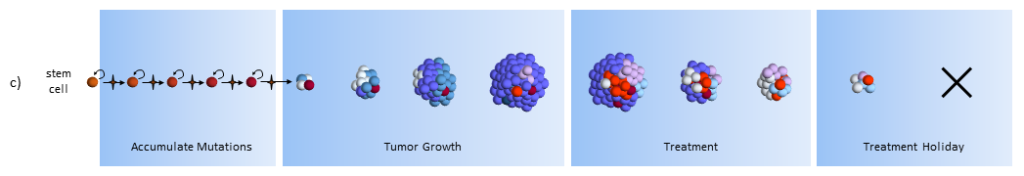

Effective chemotherapy works on most, but usually not all tumor cells. Treatment-resistant tumor cells slowly emerge and multiply. Over a period of months, the tumor shrinks quickly and may even become too small to detect on scans. NED! Time to celebrate! Done with chemo! Not so fast.

Unfortunately, chemotherapy is curative in very few of cancers, like testicular cancer2,3 and Hodgkin lymphoma3. Likely, tumor cells remain and will recur with a possibly different composition of tumor mutations. What’s a patient to do?

Effective Tumor Treatment

An effective treatment does leave you with more options.

- You have a treatment that is known to be effective against the tumor’s original composition. If there is a recurrence, you can hope that the composition is similar and try the same treatment.

- You may become eligible for surgical resection. This is the only reliable curative option for pancreatic cancers.

- An effective treatment may last for years. You have bought some time for new treatments to come online.

Implications for Treatment

I think that this is the key takeaway of this post:

cancer tumors are composed of a heterogeneous mass of genetically altered cells that don’t all respond identically to treatment.

What treatment outcomes support this model of how tumors react to chemotherapy?

The most effective treatments target mutations present throughout the entire tumor, such as one of the original set as the normal cell mutated into the first cancer cell. If you’ve had an exceptional response, perhaps your oncologist can contribute your treatment information to the NCI’s Exceptional Responders Initiative and help improve outcomes for others?

Successful treatments target mutations found in both tumor and germline DNA with the goal of eliminating the entire tumor before a resistant mutation develops. Cases like this have been demonstrated in BRCA2 pancreatic cancer patients4,5,6. A cancer panel test could identify germline mutations in many cancer-related genes.

Heterogeneity helps these tumors elude chemotherapy’s effects. In pancreatic cancers, this means that tumors treated with chemotherapy alone return and that surgical removal is the most reliable cure.

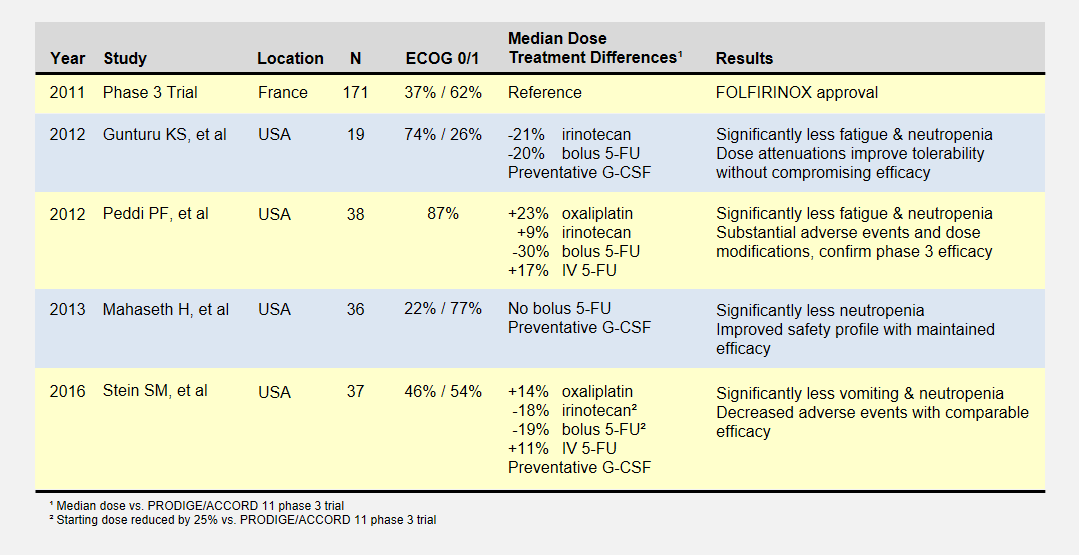

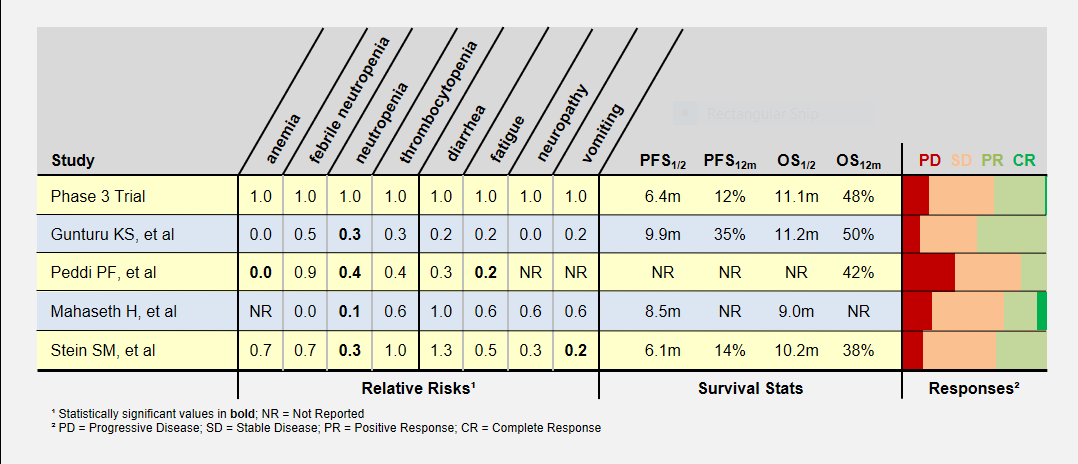

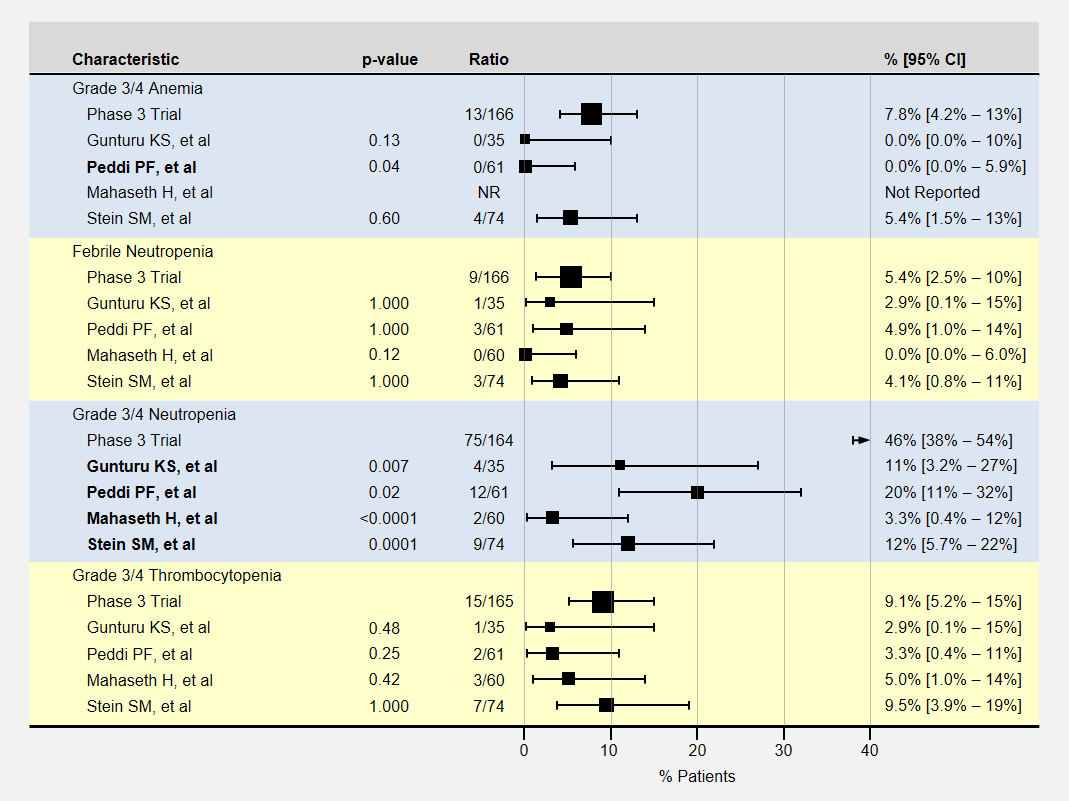

Mutational differences of tumor cells within the same tumor limits treatment effectiveness. Perhaps PanCan’s most successful chemotherapy is the four drug combination FOLFIRINOX because it targets multiple types of mutations simultaneously?

PanCan.org‘s Know Your Tumor program tests the tumor for DNA mutations. A report informs patients about treatments suspected to be effective against the identified mutations. Mostly, these treatments are only available through clinical trials, except for the important BRCA2/platinum and BRCA2/PARP inhibitor mutation/treatments combinations. Some hospitals and independent testing companies also provide this service.

The Future

I propose that every pancreatic adenocarcinoma patient have their germline (inherited) DNA tested for cancer-related mutations with pancreatic cancer panel tests like Ambry Genetics PancNext, GeneDx Pancreatic Cancer Panel, or Invitae‘s Pancreatic Cancer Panel. GetColor offers a direct-to-consumer hereditary cancer test. Some major cancer centers implement these tests for all their PanCan patients. Finding a mutations such as BRCA1 or BRCA2 greatly increasing your chances of effective treatments. More details on that in another post.

We need researchers to match tumor mutations and the effective treatments. Finding these matches is what PanCan.org’s Know Your Tumor program is all about.

When we apply chemotherapy to the tumor, evolutionary mutation changes favor cells unaffected by the treatment. Some cancer treatments try to counteract this effect by alternating between two treatments. Each treatment beats down one type of cell while allowing the others to exist, like the game of whack-a-mole. It is a delaying tactic that treats the cancer as a chronic condition always needing treatment. Pancreatic cancer does not yet have this type of treatment.

Several clinical trials are attempting to match specific mutation to treatments now. You can join in these or await the results.

Driving treatment decisions on 1 Aug 2016

References

[1]Fokas E, O’Neill E, et al. (2015). “Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: From genetics to biology to radiobiology to oncoimmunology and all the way back to the clinic”. Biochim Biophys Acta 1855(1):61-82. PMID: 25489989.

[2] American Cancer Society web page: Treatment options for testicular cancer, by type and stage: (accessed 31 Jul 2016) http://www.cancer.org/cancer/testicularcancer/detailedguide/testicular-cancer-treating-by-stage

[3] Cancer Research UK web page: How chemotherapy works: (accessed 31 Jul 2016) http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cancers-in-general/treatment/chemotherapy/about/how-chemotherapy-works

[4] Sonnenblick A, Kadouri L, et al. (2011). “Complete remission, in BRCA2 mutation carrier with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma, treated with cisplatin based therapy”. Cancer Biol Ther 12(3):165-8. PMID: 21613821.

[5] Lohse I, Borgida A, et al. (2015). “BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations sensitize to chemotherapy in patient-derived pancreatic cancer xenografts”. Br J Cancer 113(3):425-32. PMID: 26180923.

[6] Golan T, Kanji ZS, et al. (2014). “Overall survival and clinical characteristics of pancreatic cancer in BRCA mutation carriers”. Br J Cancer 111(6):1132-8. PMID: 25072261.